We spent two days in Manaus as part of our Viking Cruise. Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon basin, was not a place I ever thought I’d visit, simply for its remoteness. It’s 1000 miles inland from the mouth of the river and it is the furthest you can go along the river in a cruise ship. Its existence can be explained in one word and that is rubber.

Manaus was founded in the late 1600s at the confluence of two rivers, the River Negro and the Solimões River, forming the Amazon as we know it. The city’s heyday came in the late 1800s as a result of the rubber boom. We spent two days in Manaus, one day visiting its colonial centre and another at the meeting of the waters.

To understand Manaus, you need to understand rubber

Christopher Columbus first noted rubber on his exploration of the Caribbean and brought it back to Europe. Fellow explorers noticed that indigenous tribes used rubber to waterproof their shoes and clothes.

Dr Joseph Priestly is said to be the first person to use it as an eraser, but it was Charles Goodyear, who dropped rubber and sulphur on a hot surface, turning it black but pliable, and so the tyre was born.

Turns out there are a lot of rubber trees, Hevea brasiliensis, in the Amazon. Amazon tribes would score a tree and wait for the sap to drain. At first these tribes were enslaved to collect the rubber by settlers who were so abusive that ninety per cent of the population died out. Eventually, new harvesters were needed to be found and so the industry advertised.

Adventurers from the United States and Europe came to Brazil ready to make their fortunes. In 1906, the world consumed sixty million pounds of rubber and in total, forty million pounds came from the Amazon. Rubber plantations were actually just vast tracts of land given to people with means by the Brazilian government.

Rubber harvesters came to Brazil, not as slaves, but still penniless. Each was then schmoozed by a plantation foreman who signed them up for service and sold them supplies. Before leaving, each new harvester was presented with an invoice for the schmoozing and supplies – often it would take over a year to pay back their debt.

Each harvester would extract rubber from between 85 to 100 trees, which would then get boiled, rolled in 225 pound balls and marked with their own stamp, ready to be floated down the river for sale. At each plantation there would be a large house for the owner, an overpriced pub and a store selling exorbitantly priced goods – it was through debt that the rubber barons kept their indentured workforce.

Yungjohann – a rubber harvester

Details of the life of a harvester are primarily known through the diaries of John C. Yungjohann a Dutch-American who sailed from New York to Belem in 1896.

He came with high hopes, only to succumb to the tactics of the recruiters. By the time he reached his ‘patch’ many of the small team he’d joined had yellow fever. The recruiter abandoned the group, leaving them to build lean-tos in which to live and cook their rubber.

He was a shrewd survivor. Firstly he cut a path between the rubber trees through the dense forest to avoid getting lost and in his first year he’d collected enough rubber to almost clear his debt. He only bought the most essential supplies from the plantation shop at inflated prices, ergo increasing his debt and instead adjusted his diet to eat foods that could be obtained from the land or forest – acai berries, brazil nuts and drinking sassafras flavoured with vanilla instead of coffee.

Yungjohann eventually survived ten years in the forest repaying his debt, surviving fevers, tribal wars and an alligator attack that wiped out a whole year’s rubber crop in one fell swoop. It was his friendship with the local tribe that ensured his survival – he helped to defend women and children when other tribes attacked and they nursed him back to health when he fell ill.

In his final year, he collected nearly 4 tonnes of rubber stowed in a cave – enough to clear his debt and earn him a small fortune. However, he was so ill he was unable to ever cash it in – friends had to track him down in the forest and carry him to a steamship to go to a hospital in Barbados where he convalesced for 11 months, and never returned to his rubber stash.

Amazonas Theatre

As a result of the wealth enjoyed by the rubber barons, Manaus enjoyed a golden age. It was the second city to have electricity after Rio de Janeiro and it was also well-known that the city was a hotspot for diamond sales. As part of our tour, we visited one of the vast mansions built for the rubber barons, the Palacio Rio Negro for Karl Waldemar Scholz, in 1903.

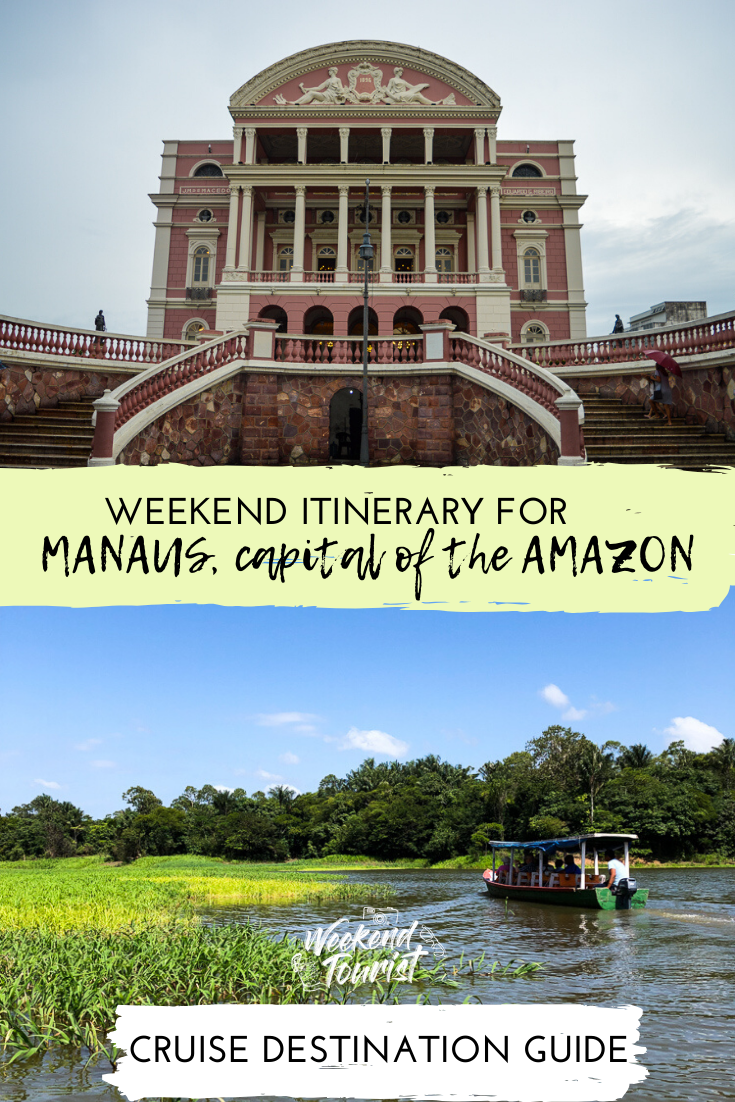

Those barons needed somewhere to get dressed up and show off their wealth. The Teatro Amazonas or Manaus Opera House was built with European marble, crystal chandeliers from Italy and tile work from France, the ballroom was floored in wooden planks from the rainforest. All at the cost of $2 million dollars.

And to celebrate rubber in all its glory, they used the substance to pave the driveway to ensure that the rattling of horse and carriages wouldn’t be heard during performances. In all their finery, rubber barons didn’t want to be too hot, so huge ice blocks were placed outside the building’s vents with giant fans ready to blow in the cold air but were so noisy they’d drown out the singers.

Unfortunately, by the time the first opera was ready to stage, half the company was plagued with yellow fever and half the cast died. The opera house remained closed for much of the century, they simply couldn’t get anyone to visit.

Outside the theatre stands San Sebastian Square which replicates the two waters of the Rio Negro and Solimões River, with the classic Portuguese two-tone tiles in an undulating design. Our next stop was the Museum of Indigenous Tribes which hosts a variety of exhibits from local peoples.

By mid-1900s, British explorer and probably what we would now call, bio-pirate, Henry Wickham stole 70,000 rubber tree seeds from under the noses of the rubber barons. The seeds were sent back to Kew Gardens who sent them to new plantations in British colonies Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore. Unfortunately for the rubber barons the seeds did amazingly well and that was the end of Manaus’s rubber boom.

Mercado Municipal

From the port, it is a short walk to the Mercado Municipal, a bustling marketplace that sells fish, tropical produce and medicinal herbs and is designed by the Eiffel workshop, the chap behind the famous Paris landmark.

With our limited Portuguese language skills, we sat down at a local cafe and ordered a round of tapioca pancakes. These were thicker than your average crepe with the thickness of a tortilla with a floury texture. The flavour came from the fillings and we tried barbecued banana, a cheese (a bit like halloumi), grilled meats and omelette. We also had grilled chorizo sausage with chips. A lunch of kings.

Meeting of the Waters

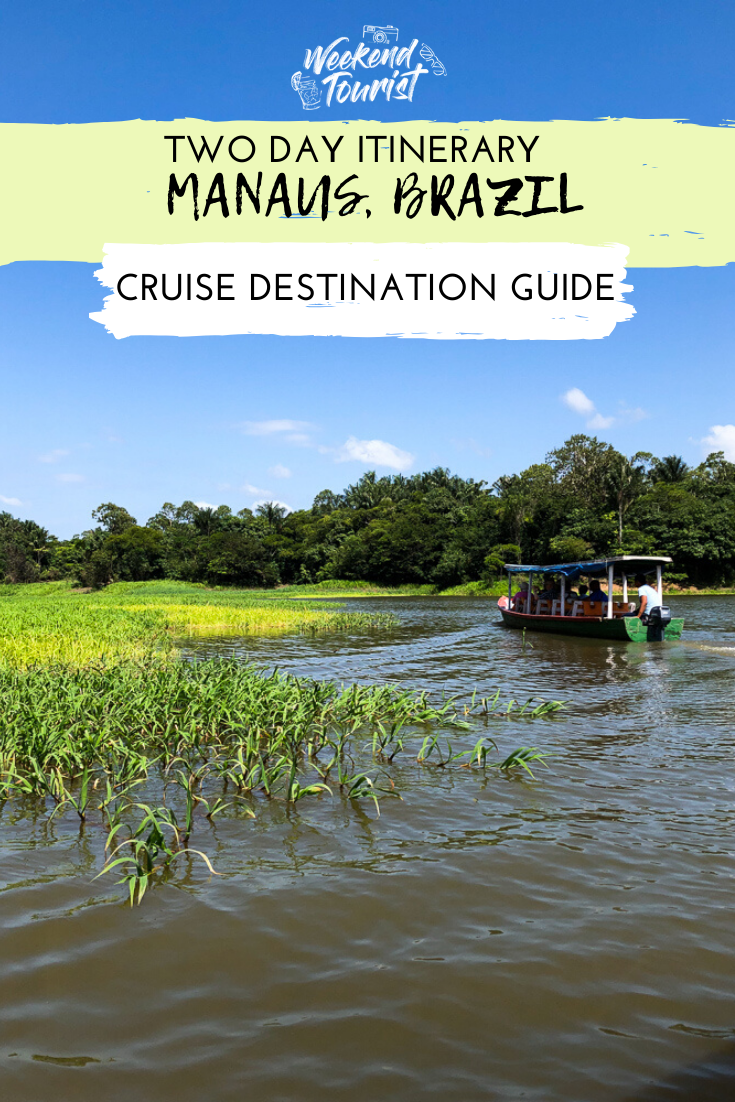

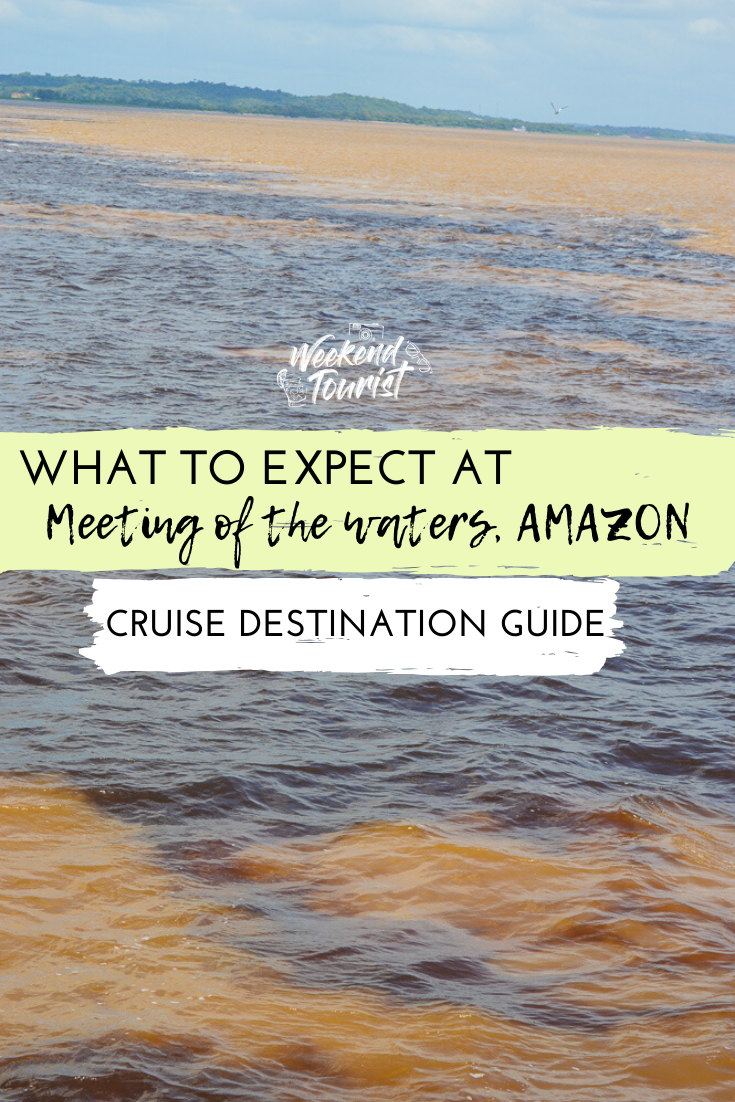

On our second day, we took a local boat to see the meeting of the waters, where the Rio Negro and the Solimões rivers meet. Here they run concurrently for several miles, the dark blue waters of the Rio Negro with the muddy waters of the Solimões river.

The water from the Rio Negro flows from the jungles of Colombia and gains its colour from the plant materials that steeps through it. The water temperature is on average 28 degrees and flows slowly.

Conversely, the Rio Solimões contains a large amount of sediment from the Andes Mountains, is cooler at 22 degrees and flows faster than the Rio Negro at 6km per hour. It’s the difference in flow rate, temperature and density that prevents the river from mixing. Downstream the river encounters several obstacles that churn the water together.

On our boat, we spotted pink river dolphins or botos, which have the largest bodies and brains of any freshwater dolphin. And they’ve adapted to swimming in murky waters of the Amazon, as their vertebrae are not fused to their necks, this means that they can turn their heads 180 degrees to manoeuvre through tree trunks and rocks after prey.

Local legend goes that at night the pink river dolphin turns in a man and has his way with innocent local women, who bear him children, before sinking back into the river.

We took about an hour to reach a lake, where we disembarked into even smaller boats like large canoes to get a closer look at river banks, seeing birds, fauna and other wildlife. The tourist centre was built as a floating house. Before heading home we walked to see the giant lilies, which we’ve seen in the Edinburgh Botanical Gardens, but never in their natural habitat.